HEPATITIS B VIRUS (HBV)

OVERVIEW

Hepatitis B is a viral infection that attacks the liver and can cause both acute and chronic disease; it is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV).

Hepatitis B is a viral infection that attacks the liver and can cause both acute and chronic disease; it is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV).

For many people, hepatitis B is a short-term illness. For others, it can become a long-term, chronic infection (lasting >6 months) that can lead to serious, even life-threatening health issues. This is because chronic HBV infection increases the risk of developing conditions that permanently scar the liver: liver failure, cancer or cirrhosis. These complications cause high morbidity and mortality. Hence, hepatitis B is a major global health problem.

Most adults with hepatitis B recover fully, even if their signs and symptoms are severe. Infants and children are more likely to develop a chronic, long-lasting HBV infection. Risk for chronic infection is therefore related to age at infection: about 90% of infants with hepatitis B go on to develop chronic infection, whereas only 2%-6% of people who get hepatitis B as adults become chronically infected. The best way to prevent hepatitis B is to get vaccinated. Vaccines can prevent hepatitis B. If you're infected, taking certain precautions can help prevent spreading the virus to others.

Signs and symptoms of HBV range from mild to severe. They usually appear at 1-4 months after infection, but they can also appear as early as 2 weeks post-infection. Most people do not experience any symptoms when newly infected; especially young children may not have any symptoms. However, some people have acute illness with symptoms that last several weeks.

HBV signs and symptoms may include:

- abdominal pain

- dark urine

- fever

- joint pain

- loss of appetite

- nausea and vomiting

- weakness and (extreme) fatigue

- yellowing of the skin and of the whites of the eyes (jaundice)

TRANSMISSION

In highly endemic areas, hepatitis B is most commonly spread from mother to child at birth (perinatal transmission) or through horizontal transmission (exposure to infected blood), especially from an infected child to an uninfected child during the first 5 years of life. The development of chronic infection is common in infants from their mothers and before the age of 5 years old.

Hepatitis B is also spread by needlestick injury, tattooing, piercing and exposure to infected blood and body fluids, such as saliva and menstrual, vaginal and seminal fluids. Transmission of the virus may also occur through the reuse of contaminated needles and syringes or sharp objects either in health care settings, in the community or among people who inject drugs. Sexual transmission is more prevalent in unvaccinated people with multiple sexual partners.

The hepatitis B virus can survive outside the body for at least 7 days. During this time, the virus can still cause infection if it enters the body of a person who is not protected by the vaccine. The incubation period of the hepatitis B virus ranges from 30 to 180 days. The virus may be detected within 30 to 60 days after infection and can persist and develop into chronic hepatitis B, especially when transmitted in infancy or childhood.

DIAGNOSIS

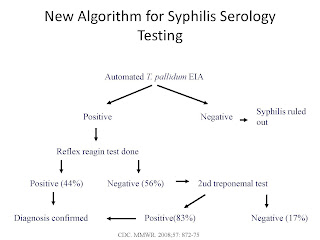

It is not possible on clinical grounds to differentiate hepatitis B from hepatitis caused by other viral agents, hence laboratory confirmation of the diagnosis is essential. Several blood tests are available to diagnose and monitor people with hepatitis B. They can be used to distinguish acute and chronic infections. WHO recommends that all blood donations be tested for hepatitis B to ensure blood safety and to avoid accidental transmission.

As of 2019, only around 10.5% of all people estimated to be living with hepatitis B were aware of their infection, while around 22% of the people diagnosed were on treatment. In settings with high hepatitis B surface antigen seroprevalence in the general population (defined as ≥2% or ≥5% HBsAg seroprevalence), WHO recommends that all adults have access to and be offered HBsAg testing with linkage to prevention, care and treatment services as needed.

Newly diagnosed with hepatitis B: Nearly 1 in 3 people worldwide will be infected with the HBV in their lifetime. If one knows having been exposed to hepatitis B, the doctor should be contacted immediately. A preventive treatment may reduce the risk of infection if receiving the treatment within 24h of exposure to the virus.

First steps

1. Understand our diagnosis. Do you have an acute or a chronic infection? When someone is first infected with HBV, it is considered an acute infection. Most healthy adults are able to get rid of the virus on their own when acutely infected. If testing remains positive after 6 months, it is considered a chronic infection. Knowing whether hepatitis B is acute or chronic helps determining the next steps.

2. Prevent the Spread to Others. Hepatitis B can be transmitted to others through blood and bodily fluids, but there are safe and effective vaccines that can protect from hepatitis B. Patients should also be aware of how to avoid passing the infection to family, household members and sexual partners.

3. Find a Physician. If chronic hepatitis B have been diagnosed, it is important to find a doctor with expertise in treating liver disease.

4. Educate Yourself. It is important that patients get the facts about hepatitis B, including what it is, who gets it, and possible symptoms, starting with "What is Hepatitis B".

Hepatitis B virus - diagnosing options and their acronyms:

- serological markers associated with hepatitis B virus infection:

- AgHBs - HBV infection; hepatitis B virus antigens detectable from incubation until 3-4 months after infection; - AgHBe - along with HBV DNA, these hepatitis B virus antigens appear in serum immediately after the usual antigens (AgHBs); these particular antigen are indicators of active virus replication;

- anti-HBc antibodies - undefined persistence; anti-HBc IgM are serum detectable a bit before the clinical debut, along with transaminases rise; indicators of acute phase;

- anti-HBe antibodies - self-limiting infections;

- anti-HBs antibodies - 4-6 months after infection; on curing; virus replication stop markers;

- HBV DNA copy-number = most sensible marker of active HBV replication.

CAUSES

HBV infection is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), which is passed from person to person through body fluids. Common ways that HBV can spread are:- Close contact: the virus can pass from the infected person to the uninfected one through blood, saliva, semen or vaginal secretions. This contamination can happen through sexual contact, sharing needles, syringes or other drug-injection equipment; from mother to baby at birth.

- Sharing of needles. HBV easily spreads through needles and syringes contaminated with infected blood.

- Accidental needle sticks. HBV is a concern for health care workers and anyone else who comes in contact with human blood.

- Mother to child. Pregnant women infected with HBV can pass the virus to their babies during childbirth. However, the newborn can be vaccinated to avoid getting infected in almost all cases. It is good to get tested for HBV if pregnant or if getting ready to become pregnant.

ACUTE VS CHRONIC HBV

HBV infection: short-lived (acute) or long lasting (chronic).

- Acute hepatitis B infection lasts <6 months. The immune system likely can clear acute hepatitis B from the body and one can completely recover within a few months. Most people who get hepatitis B as adults have an acute infection, but it can lead to chronic infection.

- Chronic hepatitis B infection lasts ≥6 months. It lingers because the immune system can't fight off the infection. Chronic hepatitis B infection may last a lifetime, possibly leading to serious illnesses such as cirrhosis and liver cancer.

The younger the age of getting HBV (particularly newborns or <5 years old children), the higher the risk of the infection becoming chronic. Chronic infection may go undetected for decades until a person becomes seriously ill from liver disease.

COMPLICATIONS

Having a chronic HBV infection can lead to serious complications, such as:

- Scarring of the liver (cirrhosis). The inflammation associated with an HBV infection can lead to extensive liver scarring (cirrhosis), which may impair the liver's ability to function.

- Liver cancer. People with chronic HBV infection have an increased risk of liver cancer.

- Liver failure. Acute liver failure is a condition in which the vital functions of the liver shut down. When that occurs, a liver transplant is necessary to sustain life.

- Other conditions. People with chronic HBV may develop kidney disease or inflammation of blood vessels.

HBV-HIV Coinfection

Some of the people living with HBV infection are also infected with HIV. Conversely, the global prevalence of HBV infection in HIV-infected individuals is around 7.4%.

Since 2015, WHO has recommended HBV treatment for everyone diagnosed with HIV infection, regardless of the stage of disease. Tenofovir, which is included in the treatment combinations recommended as first-line therapy for HIV infection, is also active against HBV.

TREATMENT

For acute hepatitis B, care is aimed at maintaining comfort and adequate nutritional balance, including replacement of fluids lost from vomiting and diarrhea.

Chronic hepatitis B can be treated with oral antiviral medication. Treatment can slow the progression of cirrhosis, reduce incidence of liver cancer and improve long term survival.

WHO recommends the use of oral treatments (tenofovir or entecavir) as the most potent drugs to suppress hepatitis B virus. Most people who start hepatitis B treatment must continue it for life.

In low-income settings, most people with liver cancer die within months of diagnosis. In high-income countries, patient present to hospital earlier in the course of the disease, and have access to surgery and chemotherapy which can prolong life for several months to a few years. Liver transplantation is sometimes used in people with cirrhosis or liver cancer in high-income countries, with varying success.

PREVENTION

Hepatitis B can be prevented by vaccines that are safe, available and effective. The available vaccines offer 98-100% protection against hepatitis B. Preventing hepatitis B infection averts the development of complications including chronic disease and liver cancer. The HBV vaccine is typically given as 3 or 4 injections over 6 months and is recommended for:

- newborns

- children and adolescents not vaccinated at birth

- people who live with someone who has hepatitis B

- health care workers, emergency workers and other people who come into contact with blood

- anyone who has a sexually transmitted infection, including HIV

- men who have sex with men

- people who have multiple sexual partners

- sexual partners of someone who has hepatitis B

- people who inject illegal drugs or share needles and syringes

- people with chronic liver disease

- people with end-stage kidney disease

- travelers planning to go to an area of the world with a high hepatitis B infection rate

ADULTS LIVING WITH HEPATITIS B

Testing positive for the hepatitis B virus for >6 months indicates having a chronic hepatitis B infection. All patients with chronic hepatitis B infections, including children and adults, should be monitored regularly, since they are at increased risk for developing cirrhosis, liver failure, or liver cancer.

An appointment should be made with a hepatologist (liver specialist) or gastroenterologist familiar with hepatitis B. This specialist will order blood tests and possibly a liver ultrasound to evaluate hepatitis B status and the health of the liver. The doctor will probably want to see the patient at least once or twice a year to monitor hepatitis B and to determine if there would be benefit from treatment.

Not everyone who tests positive for HBV will require medication. Depending on the test results, the doctor might decide to wait and monitor the condition. Whether starting treatment right away or not, the doctor will want to see the patient every six months, or at minimum once every year.

Once diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B, the virus will most likely stay in the blood and liver for a lifetime. It is important to know that one can pass the virus along to others, even if not feeling sick. This is why it's so important making sure that all close household contacts and sex partners are tested and vaccinated against hepatitis B.

The most important thing to remember is that chronic hepatitis B is a medical condition as serious as diabetes and high blood pressure that can be successfully managed if you take good care of your health and your liver. You should expect to live a long, full life.