HEPATITIS D VIRUS (HDV)

KEY FACTS AND OVERVIEW:

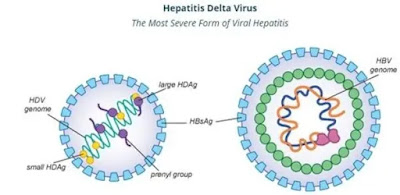

Hepatitis D virus (HDV) requires hepatitis B virus (HBV) for its replication; it affects around 5% of chronic HBV infected people.

Hepatitis D virus (HDV) requires hepatitis B virus (HBV) for its replication; it affects around 5% of chronic HBV infected people.

The combination of HDV and HBV infection is considered the most severe form of chronic viral hepatitis due to more rapid progression towards liver-related death and hepatocellular carcinoma and liver-related death. Hepatitis D infection can be prevented by hepatitis B immunization, but treatment success rates are low.

Hepatitis D: liver inflammation caused by HDV. Vaccination against hepatitis B: the only prevention method.

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION:

Geographical hotspots of high HDV infection prevalence: Mongolia, the Republic of Moldova, countries in western and central Africa.

Geographical hotspots of high HDV infection prevalence: Mongolia, the Republic of Moldova, countries in western and central Africa.

TRANSMISSION:

The routes of HDV transmission, like HBV, occur through broken skin (via injection, tattooing etc.) or through contact with infected blood or blood products. Transmission from mother to child is rare. Vaccination against HBV prevents HDV coinfection and hence expansion of childhood HBV immunization programs has resulted in a decline in hepatitis D incidence worldwide.

The routes of HDV transmission, like HBV, occur through broken skin (via injection, tattooing etc.) or through contact with infected blood or blood products. Transmission from mother to child is rare. Vaccination against HBV prevents HDV coinfection and hence expansion of childhood HBV immunization programs has resulted in a decline in hepatitis D incidence worldwide.

Chronic HBV carriers are at risk of infection with HDV. People who are not immune to HBV (either by natural disease or immunization with the hepatitis B vaccine) are at risk of infection with HBV, which puts them at risk of HDV infection.

Those who are more likely to have HBV and HDV co-infection include indigenous people, people who inject drugs and people with hepatitis C virus or HIV infection. The risk of co-infection also appears to be potentially higher in recipients of haemodialysis, men who have sex with men and commercial sex workers.

SYMPTOMS:

In acute hepatitis, simultaneous infection with HBV and HDV can lead to signs and symptoms indistinguishable from those of other types of acute viral hepatitis infections: fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, dark urine, pale-colored stools and jaundice (yellow eyes).In a superinfection, HDV can infect a person already chronically infected with HBV. HDV superinfection accelerates progression to cirrhosis almost a decade earlier than HBV mono-infected persons. Patients with HDV induced cirrhosis are at an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.

DIAGNOSIS:

HDV infection is diagnosed by high levels of anti-HDV immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM), and confirmed by detection of HDV RNA in serum. However, HDV diagnostics are not widely available.

TREATMENT:

Pegylated interferon alpha is the generally recommended treatment for HDV infection. The virus tends to give a low rate of response to the treatment, however, the treatment is associated with a lower likelihood of disease progression. This treatment is associated with significant side effects and should not be given to patients with decompensated cirrhosis, active psychiatric conditions and autoimmune diseases.

PREVENTION:

While WHO does not have specific recommendations on hepatitis D, prevention of HBV transmission through hepatitis B immunization, including a timely birth dose, additional antiviral prophylaxis for eligible pregnant women, blood safety, safe injection practices in health care settings and harm reduction services with clean needles and syringes are effective in preventing HDV transmission. Hepatitis B immunization does not provide protection against HDV for those already infected with HBV.